It’s Earth 🌎

Researchers are currently attempting to unravel the mystery behind the sudden and significant cooling of the tropical Atlantic, but they have yet to uncover many clues. “We are still puzzled by what is actually taking place,” the scientists remarked.

During a few months this summer, a large section of the Atlantic Ocean near the equator experienced a rapid cooling phenomenon. Although the cold patch is now returning to normal temperatures, scientists are still puzzled by what initially caused the drastic cooling. This unusual cold patch, which is limited to a specific area of ocean around the equator, appeared in early June after a period of unusually warm surface waters that hadn’t been seen in over 40 years.

While this region is known to alternate between cold and warm phases every few years, the speed at which it transitioned from record high temperatures to record low temperatures this time is unprecedented. A postdoctoral research associate at the University of Miami in Florida, described the event as “really unprecedented” and stated that scientists are still unsure of the underlying causes. A scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) who oversees a network of buoys in the tropics collecting real-time data on the cold patch, also expressed uncertainty about the phenomenon, suggesting that it may be a transient feature resulting from unknown processes.

Sea surface temperatures in the eastern equatorial Atlantic were at their highest in February and March, surpassing 86 degrees Fahrenheit (30 degrees Celsius) — the warmest months on record since 1982. As June arrived, temperatures started to drop mysteriously, reaching their lowest point in late July at 77 F (25 C), according to a recent blog post.

Forecasts indicated that this cooling trend could potentially develop into an Atlantic Niña, a climate pattern that typically brings increased rainfall to western Africa and decreased rainfall to northeastern Brazil, as well as countries along the Gulf of Guinea such as Ghana, Nigeria, and Cameroon. This phenomenon, which is not as strong as its Pacific counterpart La Niña and has not occurred since 2013, would have been officially declared if the below-average temperatures persisted for three months, until the end of August. However, the cold water pocket has been warming in recent weeks, it is unlikely to be classified as an Atlantic Niña.

Colder surface waters are usually accompanied by stronger trade winds, which flow near the equator and are the main factors behind La Niña events. These winds push warm surface waters away, allowing cooler water from deeper levels to rise to the surface through a process called equatorial upwelling. However, the current cold region is puzzling because it is happening alongside weaker winds southeast of the equator, which is the opposite of what would typically cause cooling.

Winds may actually be responding to the cooling rather than causing it. Strong winds to the west of the cold patch in May may have initially triggered the cooling, they have not increased as much as the temperature has dropped, indicating that there may be other factors at play. Scientists have considered various climate processes, such as intense heat fluxes in the atmosphere or sudden changes in ocean and wind currents, but none seem to be obvious drivers of this cooling event.

Although unprecedented, the recent significant cooling is unlikely to be attributed to human-induced climate change. Upon initial examination, it appears to be a natural fluctuation within the climate system in the equatorial Atlantic.” Utilizing data from satellites, oceanic buoys, and other meteorological instruments, scientists, are closely monitoring the cold patch and any potential impacts it may have on the surrounding continents, which may not be evident for several months. Scientists Said. “This could potentially have significant consequences,” “We will simply have to observe and wait to see what unfolds.”

Four things to know about a possible Atlantic Niña

Earlier this month, we wrote about a pocket of cooler-than-average surface waters that had emerged near the equator in the eastern Atlantic in June and July. The localized cool spot was interesting because if it had continued at that strength through August, it would be classified as an Atlantic Niña—a natural pattern of warm-cool swings in the eastern equatorial Atlantic that affects seasonal climate in the region.

Our plan was to wait give the August data a chance to come in and be analyzed before doing a follow-up post in early or mid-September covering whether the event formed or fizzled, what the potential influences could be on seasonal temperature and precipitation in the region, as well as some background on what we know and don’t know about why these events occur and whether human-caused climate change is expected to affect the pattern.

That post is still coming, but we are squeezing in a quick extra post because there has been a lot of interest in the event, as well as a bit of…let’s call it over-interpretation…in some corners of the internet (as well as the Climate.gov webmail inbox) that we want to tamp down if possible. In that pursuit, here are 4 things you should know about Atlantic Niñas and Niños.

#1: Atlantic Niñas and Niños don’t affect the whole Atlantic.

The June-July cold pocket hinting at a possible Atlantic Niña was located at the equator in the eastern Atlantic. The North Atlantic as a whole remains much warmer than normal. So does the tropical North Atlantic and the hurricane Main Development Region. There has been no Atlantic-wide cooling trend in the past couple of months. In fact, part of what makes the June-July cool conditions at the equator so interesting is how different that was to the rest of the Atlantic.

#2: The localized cooling that dominated the Atlantic Niña/Niño region in June-July appears to be weakening.

As we described in our first post, sea surface temperatures in the eastern equatorial Atlantic follow a counter-intuitive seasonal cycle. The region warms up through spring, but then cools in summer thanks to wind patterns that drive upwelling of deep, cool water. In June and July this typical cooling was stronger than usual. Since then, however, the cooling has weakened, as you can see in this animation of weekly sea surface temperatures compared to average.

Weekly maps of sea surface temperatures in the tropical Atlantic Ocean from May 1–August 22, 2024, compared to the 1981–2023 average. The relatively cool conditions in the eastern part of the equatorial Atlantic in June and July have weakened somewhat through August, making the possibility of an Atlantic Niña less likely. The maps have been de-trended, meaning the influence of global warming on the ocean temperatures in this area have been subtracted out. This technique gives us a better picture of how current conditions compare to the new, warmer normal of today. Without de-trending, the warm areas on these maps would look even warmer, and the cool areas would look less cool. NOAA Climate.gov animation, based on analysis of NOAA OISST data by Franz Philip Tuchen.

One criteria for Atlantic Niña is that the cool conditions must persist for at least 2 consecutive, 3-month “seasons.” In this case, that would mean May-June-July and June-July-August. Given the August weakening, it’s less likely this event will make the official cut. We will make a final call on that once we’ve had time to analyze August completely.

#3: Atlantic Niños and Niñas have regional impacts. Global impacts are less certain.

Atlantic Niños and Niñas are known to have a limited regional influence on rainfall variability in West Africa and South America. However, during the past several years multiple studies have also suggested that the impact of Atlantic Niño and Niña can reach far beyond the equatorial Atlantic, potentially influencing the development of hurricanes near the West African coast and possibly even El Niño and La Niña in the Pacific! But, not all scientists are on board with the new, global-impacts hypotheses. So, we need to let the science evolve to see if those hypotheses mature into “knowledge.”

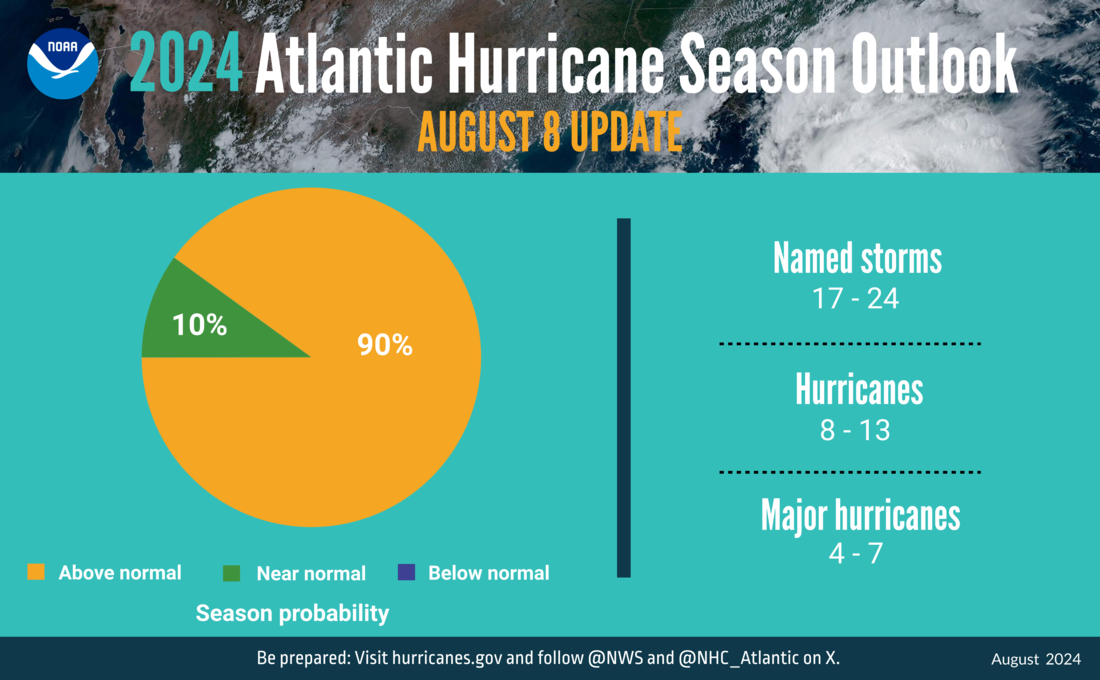

#4: The Atlantic hurricane season is still expected to be above average.

A summary infographic showing hurricane season probability and numbers of named storms predicted from NOAA’s update to the 2024 Atlantic Hurricane Season Outlook. NOAA image.

A potential connection to the hurricane season was the least emphasized, most- caveated possible impact of a potential Atlantic Niña that we mentioned in our previous post. Those “ifs” and “mights” haven’t stopped some runaway speculation. To be clear, NOAA predicts the current Atlantic hurricane season will have above-average activity. Our guest author was not suggesting otherwise. He was simply offering a little real-time speculation about how a strong, persistent Atlantic Niña—if it were to form—might influence hurricane activity.

That musing is based on the fact that a 2023 study found that the presence of Atlantic Niños (the warm phase of the pattern) increases the number of Cape Verde hurricanes. Perhaps an Atlantic Niña would have the opposite influence. But even if an Atlantic Niña were to briefly dampen activity, there remain many other factors pushing the basin toward high levels of activity. And even within an active season, there can be periodic lulls in activity. That’s the difference between climate and weather.

We are heading into the heart of the Atlantic hurricane season, so it’s as important as ever for people to remain vigilant and pay attention to the watches and warnings from the National Hurricane Center and their local weather office.